We say it here all the time: off the grid living is a lifetime commitment. If you truly want to live off the grid, you will have to constantly learn new and better ways to be self sufficient.

It’s not easy, but it’s worth it.

Fortunately there are experts like Survival Life contributor Robert Brenner to help you make off the grid living a reality for yourself and your family. Check out Robert’s tips on using straw and ice for refrigeration below.

Off the Grid Tips: Straw and Ice Make for Good Refrigeration

When I was a kid, my brother and I spent a summer with our grandparents on a farm near Quincy, Michigan. Our grandfather was a Mennonite from Canada. He emigrated (legally) and worked at a Ford plant near Detroit until he retired as a foreman in the cast iron engine block manufacturing department. After he retired, the Korean War began. As a Mennonite, he was a pacifist and avoided anything to do with war. So he bought a 90-acre farm in the center of the state. The farm could easily be made Mennonite-ready. There were electrical wires running from the power line pole out by the road passing by. My grandfather cut the wires leaving the three glass insulators shown near the peak of the roof in the photo below. He took his whole farm off the grid.

And there was a water well hand pump in front of the porch. He used horses to pull the wagons and field implements. He farmed that land and raised milk cows, chickens, and goats. It was 1950.

Years later my wife and I attended a family reunion in Ontario, Canada. While there we visited my grandfather’s childhood home. The whole area is still Mennonite country. By then another family of Mennonites were living at the old homestead. These people were still using many of the same tools and equipment my grandfather did years before. Horses pulled the wagons and farm implements. The family worked hard but seemed quite content. These people were living off the grid just like my grandparents did years later in Quincy, Michigan after he retired.

The Mennonites are devoted to a simple, sustainable off the grid lifestyle. (Image via)

When the Korean War began—Congress called it a “police action”—my grandfather went off the grid again, reverting to his Mennonite roots to farm and garden independent of government or political influence. He didn’t depend on anyone and was a great example of self-sufficient living.

My grandparents have since completed their tour on this earth and have passed on into history. A few years ago, my wife and I decided to relocate my grandparent’s farm near Quincy and see what it looks like today. To my delight, I found the farm just the same as it was in 1950s when my grandparents owned it. An Amish family lives there now—they have much in common with Mennonites. This family is also living off the grid. I was intrigued visiting with these great people, and I found it fun to see the places where my brother and I played when we were young boys. The glass insulators are still there on the side of the house up near the peak of the roof. And the well pump is still there.

Well pumps are a staple at old homesteads like these. (Image via)

But what really piqued my interest was the current resident’s discussion of refrigeration. They had cold refrigerated food all year long using an ice house and an icebox—without requiring electricity! The matriarch at the farm told me that an ice house was there when they purchased the property years ago. She said they go out each January when the surface of a nearby creek is frozen thick and cut blocks of ice out of the surface of the creek. This ice is brought by wagon to the ice house and stacked inside on a thick layer of straw. Beneath the straw is a drainage field of small rocks to allow water from melted ice to drain out into the soil. The ice is then covered with more straw below, around, and on top so ice blocks don’t touch. Each block is insulated from other blocks and the whole stack of ice is insulated from the outside environment. The ice in the storage house can remain frozen all year long through summer until winter returns and freezes the creek surface again.

An Amish ice house. (Image via)

Their ice house was a semi-underground structure built into the side of a small hill. It looked about 12 feet wide and at least this deep. Most of the sides and top were covered with earth—a berm-like building. The walls, floor, and ceiling were heavily insulated. It looked like the walls and ceiling are double-layered. I couldn’t tell if the inner-to-outer walls were insulated with straw, sawdust, or wood chips, but the structure looked well-built and solid. And it was cold inside.

In their kitchen was a simple insulated container called an “icebox” or “cold closet.” The ice box was wooden with hollow walls lined with tin and the hollow space between the walls packed with sawdust, straw, or cork. A block of ice was in a tray near the inside top of the box allowing cold air to circulate down over the food on the shelves below. This simple model had a drip pan to catch melted ice. This would be checked and emptied daily. (More expensive models would have a drain spigot coming out the bottom.)

A vintage ice box similar to the one in the story. (Image via)

When they need to refill the ice chamber, they would go into the ice house and get a block of ice. They would brush the ice off with a small broom and trim it to size. Then they placef it in the top chamber of the icebox. The melted ice is collected in a small tray and emptied daily, warmed and poured on plants growing inside the house. Their icebox kept milk, butter, meat, and vegetables fresh. An icebox like this was the primary means of refrigerating food in our country until well into the 50s. Obviously some people still use this non-mechanical, non-electrical appliance.

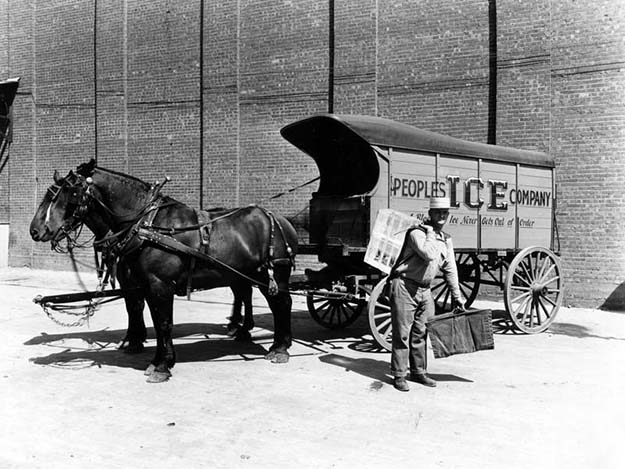

In the 40s and 50s, homes in cities had ice boxes, and ice was delivered every few days by the “ice man.” This person would ride up (or drive up) in a vehicle filled with blocks of ice. A block would be trimmed and brought into each house that had a prearranged agreement to purchase ice. The ice man would place the ice in the icebox and remove the partially melted ice. Kids used to love following the ice man’s vehicle to get shavings of ice to lick. You could tell when the ice man had been there by the melted water track leading down the street. The door-to-door delivery of ice was a social institution back then just like the milk man who delivered bottles of fresh milk to homes.

Old picture of an “ice man” delivering ice. (Image via)

When gas and electrical refrigerators were introduced, most people went “high tech.” But the name “icebox” stuck and was used to describe the refrigerator by older folks for many years.

If you live where creeks and streams freeze over, you may want to consider an ice house—even without ice it makes a good vegetable and fruit cold storage. And you may want to make or buy an icebox to keep your food cold should the grid go down and SHTF arrives. You can find some great guides and construction details on the Internet. There are also companies selling construction services or iceboxes and general refrigeration products. You “can” have cold storage without electricity!

Source:survivallife.com

Leave a Reply